Shawnee National Forest

In the southern tip of Illinois lies the rolling Shawnee Hills where 289,000 acres await you to relax, unwind and explore the Shawnee National Forest. Here you will find vast forests, wetlands and rugged bluffs home to a variety of plants and animals. The natural beauty of the area is ideal for all types of outdoor recreation.

Ways to search our Recreation Page:

- Search by Recreation Activity from the list on the left

- Zoom in on the map below and click on a site.

- Search by Recreation Site - Click on Find An Area on the right side bar

- Recreation Site Brochures and Maps

- Historical Sites & Topics

- Designated Wilderness Areas

- Recreation.gov

- Federal and State Recreation Providers

Outdoor Safety and Information:

- Forest Emergency & Safety Brochure

- Rules and Restrictions

- Area Alerts and Closures

- List of Outfitters and Guides

- Area Tourism Websites

RecAreaDirections

Open with Google Map

Misc

| Stay Limit | |

| Reservable | false |

| Keywords | |

| Map Link | |

| Contact Phone | |

| Contact Email |

Permits info

Facilities

Mississippi Bluffs Ranger District Facility

West side of the Shawnee National Forest

Lincoln Memorial Facility

The Lincoln Memorial is the site of the third in a series of seven Lincoln-Douglas debates. Currently the picnic area offers three walking loops ranging from .24 - .41 miles. Walking paths are on paved surface and surrounded with various plant and tree species. The Lincoln Memorial pond provides great scenery for walkers and a great habitat for turtles.

Camp Cadiz Campground Campground

List of CampsitesThis campground is the site of an old Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work camp. Somewhat off the beaten path Camp Cadiz is usually quiet and rarely do the campsites fill up; with the exception of turkey and deer hunting seasons. The campsites are level and each has a fire ring with grill and picnic table. Equestrian camping is allowed.

Hidden Springs Ranger District Facility

East side of the Shawnee National Forest

Simpson Barrens Natural Area Facility

Simpson Township Barrens is a unique ecological area containing several native plant communities such as limestone barrens, seeps, dry and dry-mesic upland forest, an intermittent creek drainage and support a rich diversity of plants. The limestone barrens communities are characterized by very dry, calcium rich soils that support a flora more commonly encountered on the tall grass prairies found north of the Shawnee National Forest. At the Simpson Township Barrens Ecological Area two limestone barrens are located within a matrix of dry and dry-mesic upland forest each with a southwestern aspect. The dry and dry-upland oak forests are dominated by post oaks (Quercus stellata), white oaks (Quercus alba) and black oaks (Quercus velutina). pignut hickory (Carya glabra), and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa) are also commonly encountered. Unlike the barrens community the forested matrix is characterized by sandstone cliffs, sandstone boulders and other sandstone rocks giving the soils a somewhat sandy consistency. The soils are acidic and support a flora completely different from the limestone barrens.

Clear Springs Wilderness Facility

Located in Union and Jackson Counties, Clear Springs Wilderness offers some great opportunities to view the Mississippi River Valley. Elevations range from 400 ft. to over 900 ft. The Area is generally regarded as rough terrain, with narrow ridgetops, steep slopes and narrow creek bottoms. Trails for hiking and equestrian use will take you by some indications of past use by people including homestead, fruit trees, cemeteries and abandoned roads. Bald Knob Wilderness also includes The Hutchins Creek Wild and Scenic River Study Corridor. The Wildernsess also lies adjacent to LaRue-Pine Hills Ecological Area.

Lusk Creek Wilderness Facility

Lusk Creek Wilderness is located in Pope County. The wilderness features an outstanding scenic view called Indian Kitchen (Lusk Creek Canyon Nature Preserve). Trails for hiking and equestrian use will take you by some indications of past use by people including homestead, fruit trees, cemeteries and abandoned roads. Canoeing is very a popular activity on Lusk Creek during the spring and early summer. Camping along the creek is discouraged because of the probability of flash flooding. Also, camping is not allowed in Lusk Creek Canyon Nature Preserve. Located adjacent to Lusk Creek Wilderness is the East Fork Special Management Area. This area is designated to become a wilderness all its own. The Illinois Wilderness bill has designated East Fork to become a Wilderness area in late November, 1998.

Bay Creek Lake Facility

Bay Creek Lake is located in Pope County and lies south of Jackson Falls Area. Access is by gravel and dirt roads, but the road does become impassable and therefore portaging a canoe or kayak is necessary to reach this lake. The clear clean waters of Bay Creek Spring that feeds the Lake make it worth the trip.

Burden Fall Wilderness Facility

Burden Falls Wilderness is located in Pope County. The Wilderness is located adjacent to Bay Creek Wilderness and is in a stone's throw of Bell Smith Springs Recreation Area.Burden Falls Wilderness is comprised of a central hardwood ecosytem with some pine plantations. Trails for hiking and equestrian use will take you by some indications of past use by people including homestead, fruit trees, cemeteries and abandoned roads. Of course, there is a small, but very scenic waterfall located on the southern edge of the wilderness.

Underground Railroad: Crow Knob Facility

In the mid-1800s the landscape that is now the Shawnee National Forest provided paths to freedom for runaway slaves. After crossing the Ohio River into Illinois, the dense forest and rugged terrain helped fugitives stay hidden during their perilous journey toward liberty.

Crow Knob is a sandstone bluff that overlooks the former Miller Grove community to the south. Because of its vantage point, it served as an important lookout for the Underground Railroad. According to local myth, fires were lit on top of the bluff to signal and guide freedom seekers toward a safe zone in Miller Grove. Hiking to crow knob may be difficult. Please consult with the local Forest Service office for more information.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Mary McCorvie, “Spotlight on the Underground Railroad,” http://www.recreation.gov/marketing.do?goto=acm/Explore_And_More/exploreArticles/Spotlight__The_Underground_Railroad_on_the_Shawnee_National_Forest.htm

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: Cultural Landscape Miller Gr Facility

The American Missionary Association (AMA) was founded in Albany, New York on September 3, 1846 as an Eastern nonsectarian benevolent society that advocated radical abolitionist principles. Among its founding members included those who aided in the defense of the Amistad captives in 1839. The AMA helped put the abolishment of slavery onto the national political agenda.

Although it was a national association, the AMA focused its financial and other resources to help Border States (where free and slave states adjoined) operate the Underground Railroad. The region of southern Illinois, including today’s Shawnee National Forest, proved vital to their cause and became a focal point. The letters of James West, an AMA preacher, confirm that Pope County and Miller Grove were a hotbed of anti-slavery activity.

Over 300 missionaries, called “colporteurs,” were stationed throughout southern Illinois which they referred to as “Egypt.” They arrived there with aspirations of changing the hearts and minds of local citizens by preaching and passing out Bibles. They also distributed antislavery literature including their own magazine, the American Missionary, published from 1846 through 1934.

Literacy and education was a focus of the AMA. They believed that the anti-literacy laws perpetuated slavery by enslaving minds as well as bodies. During the Civil War the AMA began to build schools for freedmen. By 1866, they had chartered seven higher education institutions for African Americans and helped in the establishment of Howard University.

In 1934, the Board of Homeland Ministries absorbed the AMA. It was taken over by the by the United Church Board of Homeland Ministries in 1987.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Vickie Devenport and Mary R. McCorvie, “Dear Brother Tappan: Missionaries in Egypt and the Underground Railroad in the Shawnee Hills of Southern Illinois.”

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: Pope County Courthouse Facility

The town of Golconda, Illinois, was a town of contradictions during the nineteenth century. Although some community members were a part of the Underground Railroad and provided a safe haven for runaway slaves, others in the town perpetuated the hostilities and dangers facing the fugitives.

Since Golconda served as a known destination on northern escape routes, the town’s jail became the detention site for those captured in the region. Fugitive slave notices were often printed in Golconda Weekly Herald newspaper. However, in the Golconda Courthouse, migrating African Americans could post the state-mandated $1,000 bond to secure their freedom.

In 1860, the Golconda Weekly Herald described continuous violence and the danger that loomed for freedom seekers and locals who aided in their escape through Illinois. Almost every issue contained reports of abuses and threats of tar and feathering for local abolitionists.

William Hall was an escaped slave who referenced Golconda as a major point on his flight toward freedom during his fourth escape attempt. When describing the tribulations of his journey he recalled “I travelled three nights, not daring to travel days, until I came to Golconda, which I recognized by a description I had [been] given on a previous attempt.”

In the heart of today’s Shawnee National Forest, Golconda is 15 miles from the former Miller Grove which was a free Black community amidst the turbulent times of the mid-1800s.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance.

Benjamin Drew, The Refugee: Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada.

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: Sand Cave Facility

The topographical features of today’s Shawnee National Forest played a crucial role in the Underground Railroad in the mid-19th century. As slaves escaped and headed north, the dense forest and rugged terrain offered natural hiding places. On the route through Pope County, Illinois, freedom seekers often used Sand Cave for shelter and protection.

Sand Cave is located a few miles west of Crow Knob and north of the Miller Grove Community location. Unlike the high lookout point of Crow Knob, Sand Cave was a deep, dark, and secluded shelter inside the sandstone face.

Other topographical features on the Shawnee National Forest that may have been used as hiding spots along the Underground Railroad include Ox-Lot, Brasher Cave, and Fat Man’s Squeeze.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Mary McCorvie, “Spotlight on the Underground Railroad,” http://www.recreation.gov/marketing.do?goto=acm/Explore_And_More/exploreArticles/Spotlight__The_Underground_Railroad_on_the_Shawnee_National_Forest.htm

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: People of Miller Grove Facility

The Miller Family

The community of free African Americans in Pope County, Illinois came to be known as Miller Grove, presumably named for one of four families that settled the area.

In 1844, the Miller family helped establish a small community of rural dispersed farmsteads. Harrison Miller - the founder and patriarch of the town - brought his wife Lucinda and their three children from a Tennessee plantation to the woodlands of Pope County.

Although Harrison and his immediate family could not read nor write, education was important to him and the community of Miller Grove. Harrison served as an executor for a nearby former slave owner’s estate; later he became the owner and the land was used for the Mt. Gilead African Methodist Episcopal Church as well as a school. Sadly, the original log church burnt down in 1918.

In 1860, the census showed Julia Singleton as a Black schoolteacher. Julia was a freed African American from Peter Singleton, one of the four original Miller Grove families. Archeologists recently found writing slates at Miller-connected sites.

Harrison and Lucinda’s eldest son, Bedford, arrived in southern Illinois as a child and continued to live in the Miller Grove community until his death in 1911. Bedford married Abby Gill and they had four daughters. Their graves can be seen in the cemetery among a hundred others, the only lasting element of Miller Grove in today’s Shawnee National Forest.

Other Millers included Andrew Miller and his sister, Matilda, who moved from a Tennessee plantation after being granted freedom from their owner.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Vickie Devenport and Mary R. McCorvie, “Dear Brother Tappan: Missionaries in Egypt and the Underground Railroad in the Shawnee Hills of Southern Illinois.”

“Miller Grove, Pope County, IL – Underground Railroad,” http://www.southernmostillinoishistory.net/miller-grove-community.html

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: Shawnee National Forest Facility

The Underground Railroad was a vast but secret network of travel routes and safe havens to help fugitives escape slavery, most heavily travelled between 1820 and 1865.

Those escaping the slave state of Kentucky likely followed a route northwest by crossing the Ohio River into southern Illinois. Despite its Free State status, there was still hostility toward African Americans in the region, making it dangerous territory for freedom seekers and abolitionists.

To avoid detection, escapees avoided cities and took to the forests and rural routes to reach freedom, some travelling through what is now Shawnee National Forest. Although many continued north, the region of the Shawnee National Forest that lies mostly in Pope County appears to have been a vital point in the Underground Railroad. Here, a free Black community found a home in Miller Grove.

The pioneers of Miller Grove originated primarily from Tennessee. After they gained their freedom, four families settled the Miller Grove area, some traveling alongside their former masters and their families. The free people of Miller Grove built schools and churches among their homes and carved out a new life.

Often free communities like Miller Grove became part of the Underground Railroad. Community members of Miller Grove and surrounding towns served as “conductors” and helped runaways make the terrifying escape to freedom.

Today, there is little left of Miller Grove. However, natural landmarks on the national forest - Ox-Lot, Sand Cave, Crow Knob, Brasher Cave, and Fat Man’s Squeeze - remain as markers of the former community and its Underground Railroad activity. The cemetery with over 100 graves is used for ongoing research, along with Pope County tax records and other legal documents.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Mary McCorvie, “Spotlight: the Underground Railroad on the Shawnee National Forest,” http://www.recreation.gov/marketing.do?goto=acm/Explore_And_More/exploreArticles/Spotlight__The_Underground_Railroad_on_the_Shawnee_National_Forest.htm

Underground Railroad: Dabbs Family Facility

During the original migration, four former slaveholding families trekked alongside recently freed African Americans to the Miller Grove settlement in Pope County, Illinois, in today’s Shawnee National Forest.

Joseph Dabbs headed one of the four White families. With the help of Henry Sides, a fellow former slave holder, Joseph purchased the $1,000 bonds to bring each of his manumitted slaves to Illinois as free men, women, and children.

Edward (Ned) Dabbs was one of Joseph’s manumitted slaves (it was common for free Blacks to keep the names of their former white slave families). Ned married Dolly Sides in April, 1848, and the couple continued to live in the community. Unlike a majority of the adults at Miller Grove, Ned was literate. The community cherished his skills and his service as a reader and disseminator of information throughout the settlement.

Ned also became involved in the abolitionist movement with the American Missionary Association (AMA). In 1864, he submitted a handwritten request for AMA’s antislavery literature. The literature, along with letters left by James West, imply that members of the community - possibly including Ned himself - were active in the Underground Railroad.

Joseph Dabbs left one-third of his estate to Ned in his will. When Ned died in 1866, his personal effects included a large collection of books and farm animals. However, Ned acquired these belongings himself - they were not inherited from Dabbs - and attest to the life he lived after gaining his freedom.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Vickie Devenport and Mary R. McCorvie, “Dear Brother Tappan: Missionaries in Egypt and the Underground Railroad in the Shawnee Hills of Southern Illinois.”

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: James M. West Facility

Besides free African-Americans, white abolitionists also settled in the area of today’s Shawnee National Forest. James M. West resided about three miles south of Miller Grove and much of what is speculated about the community’s involvement in the Underground Railroad comes from a collection of West’s letters. The letters are mostly correspondence between himself and members of the American Missionary Association (AMA).

James West was a strident abolitionist and a preacher for the AMA. Along with passing out bibles and antislavery literature, he preached antislavery ideology. He was not naïve about his work - his father, a Methodist preacher who laid the foundation for James’s antislavery fervor, had been killed because of his views. Originally from Kentucky, West eventually moved his wife, Sarah, and their children north to Illinois after he was persecuted and abused in his hometown.

In October 1856, the family settled in Pope County, Illinois, where West taught school for a short time. In a letter to the AMA, he recognized the irony of being the only radical abolitionist teacher employed in the region that, although a Free State, held vehement hostility toward African Americans. Despite these hostilities, West continued to preach throughout the county for people to reject slavery and accept Free Blacks into their communities. His letters to the AMA board members mentions his “friends” in the region which most likely refers to the African American community at Miller Grove.

Although mentioning specific information about the Underground Railroad could have jeopardized the operation, his letters discuss the region as a good “second depot” and “railroad.” In his letters with Brother Jocelyn of AMA, he explains that the proximity to the river was ideal and requested additional resources and AMA members to help.

In 1860, James reported to AMA that “colporteurs” (someone who distributes religious or similar literature) were in danger in the region for aiding fugitive slaves and promoting abolition. West noted in the report that “persecution is raging here to an alarming extent” and those in the area who defied the Fugitive Slave Act were often threatened with tar and feathering.

For his views, West received threats of lynching, as did another local AMA colporteur, James Scott Davis. Davis, who arrived in Pope County in 1860, lived near Broad Oak and played a vital role in disseminating antislavery literature to Miller Grove. In 1861, threats eventually drove West and Davis to flee Pope County.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Vickie Devenport and Mary R. McCorvie, “Dear Brother Tappan: Missionaries in Egypt and the Underground Railroad in the Shawnee Hills of Southern Illinois.”

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Underground Railroad: Henry Sides Facility

After crossing the Ohio River into Illinois, runaway slaves were able to take their first glorious step onto free soil. The terrifying and arduous journey toward freedom not only exacted a tremendous toll on their bodies and spirits, but also required money that they often didn’t have. The State of Illinois required a $1,000 bond for any free person of color to enter.

Freedom seekers saved or collected money for the bonds, but often still needed help. Henry Sides provided such help and served as the liaison and mediator between the courts and the freed individuals. He became a vital link between the African Americans and the community of Miller Grove and Pope County.

Henry Sides and his wife, Barbara, arrived to Miller Grove alongside the original four migrant families. Sides was a white former slaveholder in Tennessee, but when he left the state he manumitted all of his slaves and posted their bonds to enter Illinois. True to his Presbyterian and political beliefs, Sides worked and lived side by side with free Blacks in the community.

Despite being beaten and robbed (likely because of the bond money they held) Henry and Barbara continued to contribute substantial sums of money to post bonds for incoming African Americans. In his will, Henry bequeathed all of his property to a free African American, Abraham Sides.

The Sides were buried in the Miller Grove cemetery – located in today’s Shawnee National Forest – where visitors can see their graves today.

Sources:

Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: the Geography of Resistance

Mary McCorvie, “Spotlight on the Underground Railroad,” http://www.recreation.gov/marketing.do?goto=acm/Explore_And_More/exploreArticles/Spotlight__The_Underground_Railroad_on_the_Shawnee_National_Forest.htm

This information about the Underground Railroad is part of a geo-located multi-forest interpretive program. Please contact the U.S. Forest Service Washington Office Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Resources program leadership with any questions or to make changes. SGV – Recreation Data and Information Coordinator.

Bay Creek Wilderness Facility

Bay Creek Wilderness is located in Pope County. The Wilderness is located adjacent to Burden Falls Wilderness and is in a stone's throw of Bell Smith Springs Recreation Area. Bay Creek Wilderness is comprised of a central hardwood ecosystem with some pine plantations. Contained in the Wilderness is the Bay Creek Wild and Scenic River Study Corridor. Trails for hiking and equestrian use will take you by some indications of past use by people including homestead, fruit trees, cemeteries and abandoned roads.

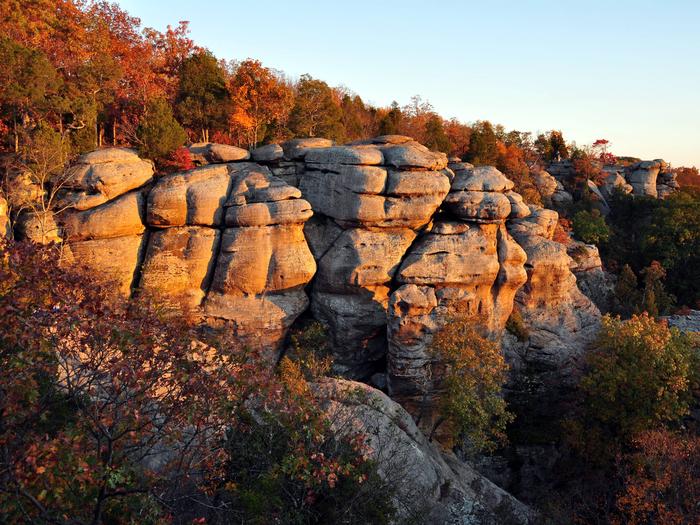

Garden of the Gods Wilderness Facility

Garden Of The Gods Wilderness is located in Saline, Pope, and Hardin Counties. The wilderness features an outstanding scenic views along with very unusual rock formations. Trails for hiking and equestrian use will take you by some indications of past use by people including homestead, fruit trees, cemeteries and abandoned roads. Being adjacent to the Garden of the Gods Observation Site, this wilderness is the most popular of Shawnee's Wilderness area's. Eagle Creek Special Land Management area (adjacent to Garden of the Gods) is designated to become a wilderness all its own. The Illinois Wilderness bill has designated Eagle Creek to become a Wilderness area in late November, 1998.

Historical Sites & Topics Facility

This region has been occupied for centuries and evidence of its past people and their culture can still be found hidden in the shawnee hills today.

For a list of Historical Sites expand Outdoor Learning section at the bottom of this page.

Preserving and Protecting Historical Sites

Archaeological sites throughout southern Illinois can provide important insights and knowledge about the past that can not be gotten elsewhere. The aritfacts contained in the sties can help us learn about little known aspects of our history, cultures and people not as well represented in current hisroty books. They are the clues left behind byt he past inhabitants that can help archaeologists determine who was living at the site, when they were living there and what they were doing. It's important that archaeologists find artifacts in their original location to accurately interpret the story of the past. When people remove artifacts from sites it destroys the ability for archaeologists to reconstruct the histories and lifeways of the people who once occupied the site.

Help us preserve our rich history by leaving archaeological sites undisturbed and report any looters or evidence of looting activities to your nearest Ranger Station.

CuteCamper

CuteCamper